Access to Justice Fellow advocates for an end to mass incarceration

When John Bowman read The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, Michelle Alexander’s sobering New York Times bestseller about America’s criminal justice system, for his book club, he was shocked. He was semi-retired after working as an attorney for 46 years, a third of which were connected with civil legal services. Yet so much of what he was reading was new to him.

When John Bowman read The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, Michelle Alexander’s sobering New York Times bestseller about America’s criminal justice system, for his book club, he was shocked. He was semi-retired after working as an attorney for 46 years, a third of which were connected with civil legal services. Yet so much of what he was reading was new to him.

“I said, ‘How, as a lawyer, did I not know any of this?’ I wasn’t sure what I could do,” he says.

John began his legal career with the Boston Legal Assistance Program. Known today as Greater Boston Legal Services (GBLS), the then-new program placed lawyers in neighborhoods around the city, where they worked in teams of two alongside a legal secretary and a community organizer. Their offices were open to residents seeking legal advice and services related to family law, housing, eviction, and other civil matters.

Throughout his legal career, John also served as a Clinical Teaching Fellow at Harvard Law School, an Associate Professor at Boston University School of Law, an Assistant Attorney General of the Commonwealth, and took other roles in the state government. He says he retired “in stages,” working part-time in a municipal law practice and as a Health Connector hearing officer after he left the state government in 2005.

After he finished The New Jim Crow, John started researching more about the main thesis of the book, which is that the criminal justice system in this country uses the War on Drugs and other tools to enforce traditional and new modes of discrimination against African American men by imprisoning them at an astonishingly high rate. John also looked into the many barriers that African American men and women face even after they have served their time and been released.

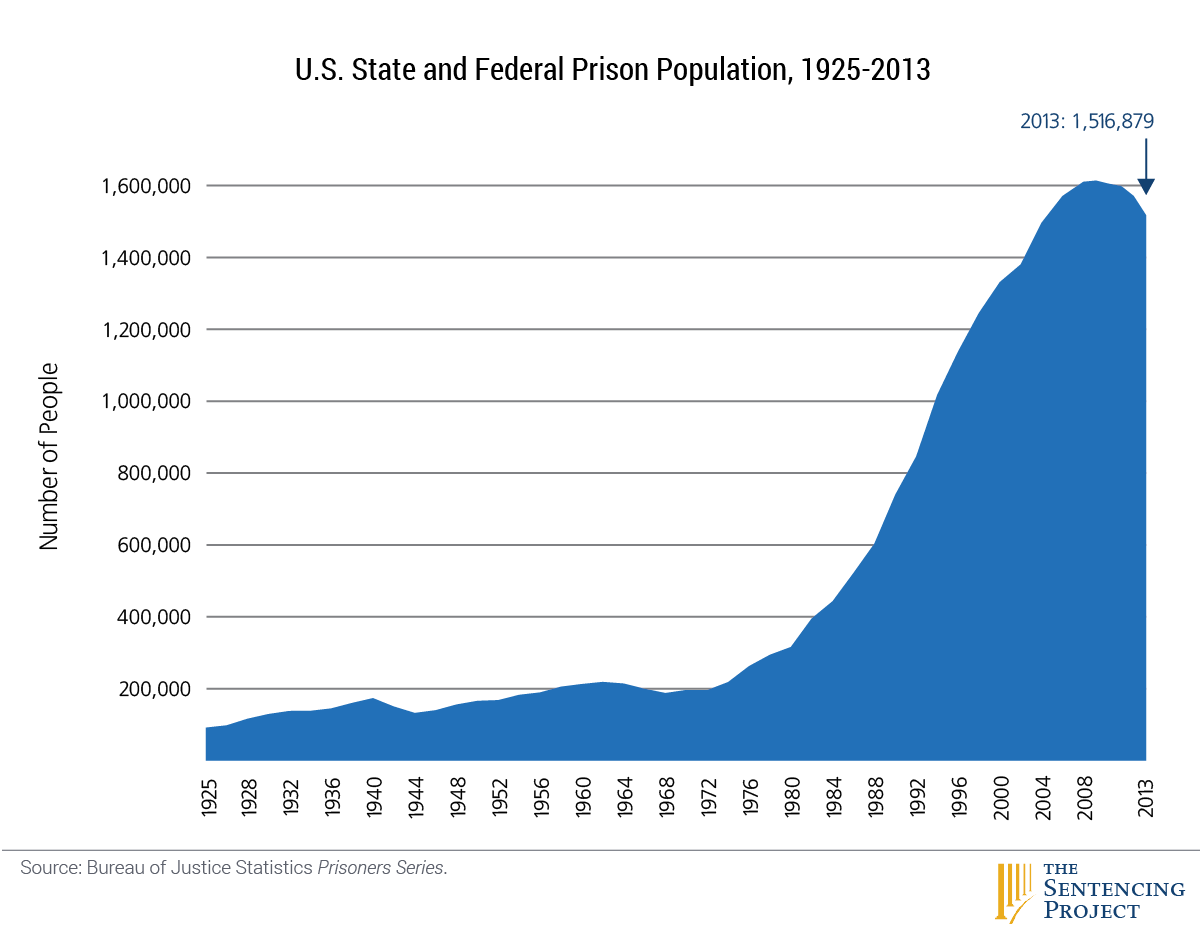

The United States prison population began a steep, decades-long increase in the 1970s, with the adoption of harsher sentencing laws, such as mandatory minimum sentences for people convicted of certain crimes, mainly related to drugs. Mandatory minimums overloaded the prison system with low-level, non-violent offenders. Today, with only 5% of the world’s population but over 25% of the world’s prisoners, the United States has been called “the world’s largest jailer” by the American Civil Liberties Union.

At around the same time that mandatory minimums caught on, states (under pressure from the federal government) started enacting laws restricting ex-prisoners. Once released, these men and women found themselves barred from receiving food stamps, public assistance, public housing, and student loans, while also facing roadblocks in accessing driver’s licenses, getting jobs, and voting.

While conducting further research, John got involved with the Jobs Not Jails Coalition, an umbrella organization connecting over a hundred social organizations, unions, and faith communities invested in reforming the criminal justice system in Massachusetts. Through Jobs Not Jails, he found himself once again using his expertise to work with vulnerable populations.

Around this time, John received a phone call from Martha Koster, a Member at Mintz Levin who helped found the Access to Justice Fellows Program – now operated by the Lawyers Clearinghouse – and who served as a Fellow during the program’s first year.

Martha asked if he would consider signing on with the program and he told her about his interest in criminal justice reform and his recent work with Jobs Not Jails. He became an official Fellow with the Jobs Not Jails coalition in September 2015 when the Fellows Program kicked off its fourth year.

John says he does a little bit of everything as an Access to Justice Fellow. He researches important bills related to criminal justice in Massachusetts, tracks them as they move through the legislative process, meets with state legislators, has given testimony at a public hearing before the state Sentencing Commission, helps the coalition expand its outreach, and works alongside other organizations within the Jobs Not Jails umbrella. He has even started a group at his church, encouraging fellow parishioners to get involved.

Throughout his Fellowship, John has collaborated extensively with a group called Ex-Prisoners and Prisoners Organizing for Community Advancement (EPOCA), which he considers one of the core components in the fight for reform.

“[Ex-prisoners] bring very interesting insight to this and I’ve learned a lot,” he says. “I’m very respectful of them and what they’ve accomplished and the fact that they’re out there trying to make things better for other people.”

One of the most important pieces of legislation Jobs Not Jails, EPOCA, and other organizations have tracked this year is Senate Bill 2021, part of an omnibus bill known as the Justice Reinvestment Act, which comprises multiple proposals for reforming the criminal justice system.

Supporters of S.2021 seek to repeal a 26-year-old law that requires the Registry of Motor Vehicles to automatically suspend, for up to five years, the license of any person with a drug-related conviction. Annually, over 7,000 people in Massachusetts have their license suspended under this law. They must pay a $500 fee to have it reinstated, and many ex-prisoners struggle to come up with the money due to difficulties finding steady employment. Governor Charlie Baker is expected to sign the bill into law once it receives final approval from the Senate.

“The driver’s license bill could be a great success and affect a lot of people positively, and it should do a lot to enhance the employability of former prisoners,” John says.

John intends to continue his work with Jobs Not Jails even after his Fellowship ends in June. He believes more bills within the Justice Reinvestment Act will appear in the legislature over the next few years and says he’s excited about the work he has been able to do through the Fellows Program.

“It can be very isolating to retire and this program gives people a whole new way to engage,” he says. “I get to sit down with other Fellows, talk about these problems, try to unravel them and do something good about them; it’s a great thing.”